One for the books, by Joe Queenan. New York: Penguin, 2012.

Joe Queenan is an inveterate reader, and has quite definite opinions on reading, and on the finite length of the rest of his life, and on what he's decided he no longer has time to read. Books give his life structure, memory and colour. This is a lovely book about the meaning of reading, particularly of reading print books (there's a refrain of You couldn't do that with a Kindle). While I can disagree with him quite passionately on his love for Proust and his disdain for To kill a mockingbird, I love his endeavour here. And as anyone who remembers his broadcasts on popular culture will know, the guy is seriously funny so even while you're disagreeing with him, you're smiling at his invective.

Entry Island, by Peter May. London: Quercus, 2014.

This is the best book I've read this year so far. Sime (pronounced Sheem) is brought in as the only English-as-a-first-language detective investigating the murder of a man on a remote island in Québec province. All evidence points to the wife as the murderer, but Sime is thrown off-balance by the strong belief that he has met the woman before. Sime's job is complicated further by his soon-to-be-ex-wife also being present on the investigating team, and by his insomnia punctuated by dreams derived from his great-great-grandfather's diary, also from a remote island but this time in the Hebrides. The stories intertwine and disorient the reader to the extent that sometimes we, like Sime, forget which time and place we're in. May does an amazing job here and it's a spellbinding read.

Danubia, by Simon Winder. London: Picador, 2013.

I'm not sure how much more knowledge of the Habsburgs I've managed to absorb in this really engaging canter through their history, but I definitely enjoyed the ride. Winder is an enthusiast for all things Central and Eastern European, and uses visits to present-day places to show the history, and often the multiple renamings, of towns and regions. He also picks up on quirks - the Habsburg jaw, the presence of improbable museums and so on - as repeating motifs. I think what I most like about this book is that he's just wandering the areas (mostly on public transport) sort of bumping into his subjects everywhere, while illustrating quite powerfully the history of conflict, nationalism, rootlessness, fecklessness, monomania and inbreeding which characteristed the dynasty. And oh, those poor, poor women, sacrificed on the altar of male primogeniture and slaughtered like cattle through childbirth. And despite this last sentence, this is a profoundly humorous, humane book.

The child who, by Simon Lelic. London: Picador, 2012.

Twelve-year-old Daniel Blake has killed his schoolmate Felicity Forbes in Exeter. This is stated very near the beginning of the book, and this isn't really a detective story; it's more an exploration of the effect of a brutal crime on the families involved, including the families of the legal and law enforcement professionals brought into a case. Leo Curtice, a local solicitor, is brought in to represent Daniel, and is unprepared for the public fury the case has unleashed and its effect on his family. It's very difficult to put this book down; the sense of one crime rotting its way through families and relationships is very powerful, and the ending is definitely worth waiting for.

We are here, by Michael Marshall [audiobook]. Read by Jeff Harding. Oxford: Isis, 2013.

Really not sure what to make of this. (I've had this problem with Michael Marshall's books before). The premise is instantly grabbing and somewhat creepy - we're introduced to a number of people who are having strange and inexplicable moments in their lives; a woman whose book group companion feels as if she's being followed but can see nothing; a man who encounters strangers in Union Park in New York who seems to be fading in and out... It's all really engaging, and you keep listening; but I don't really feel at the end as if I worked out what was going on. This is one listened to in bits over several weeks, though, so it may be my attention span, rather than the writer's ability, which is at fault.

Sunday, March 30, 2014

Saturday, March 15, 2014

Grand day out: Saltaire

So, I went on PodRetreat in February, and I have photos; but striking while the iron is still reasonably luke-warm, this was last Friday's slightly mad day trip.

Just after Christmas, East Coast had a sale; a ridiculously good sale. Wasn't able to pin family down to dates within the timescale, and there weren't many trains on a Sunday in the offer, so I thought "Wonder how far I can go for £5 each way?" and the answer was York or Leeds. I love York; but I love Leeds more, and all I've done there for the last many years is change train, occasionally popping out of the station for a quick meal between journeys.

I set off at 5:35am from the village (first train out; only the second time I've done that), so by 9:30 I'd got to Leeds, bought my onward ticket, and wandered out to City Square.

As you can see, it's a bit wet; but the forecast for the rest of the day was good. And there was a happy sight on the way out of the station; Leeds is seriously cheerful about the Grand Départ in July.

(This year, I'm abandoning the French pronunciation of Grand and doing it in a Yorkshire voice in my head...)

Normally, I'm really organised on a visit; this time, other than the tiny map in the Kindle version of the Rough Guide and a quick look-up of bus routes, I was entirely unprepared for the trip after what had felt like an extraordinarily long week. I also have absolutely no sense of direction, which is always interesting in a strange city, even one I visited briefly last year. But I had a destination in prospect, and Leeds has lots of maps around at road junctions, so I found the bus stop, and the no. 1 bus; and I reached my destination about 2 minutes before it was due to open. Looked promising!

The extremely nice Baa Ram Ewe (Headingley branch); just opposite a big shopping centre, but based in a converted cottage; about 15 minutes from the city centre by bus. The person in the shop was American, and lovely, and I realised afterwards we hadn't exchanged names (sorry, lovely yarn-shop lady!); conversation ranged from London commuting to Yarndale to the beautiful yarns they had from West Yorkshire Spinners.

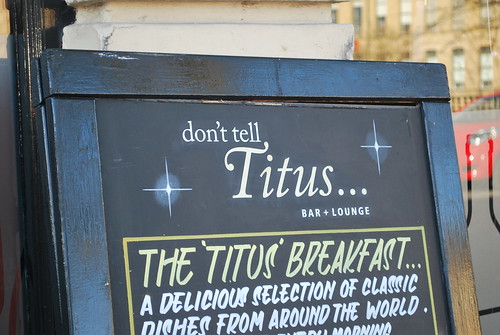

One of my aims was to fondle some of their own Titus yarn, as I hadn't managed to get anywhere near their booth at Yarndale, particularly given my final destination. A skein of duck-eggy-green, very springlike (Bramley Baths), has accompanied me home, along with a coordinating Crazy Zauberball; once the current knitting project is done that'll be the next thing on the needles! (Also picked up some gift yarn and a couple of skeins of discounted Colinette.)

All yarned-up, I got the bus back into Leeds and a train out to Saltaire. I've been through Saltaire so many times on the way to Keighley for the SkipNorth holiday, and every time I've promised myself that next time... I'd stop. But I've always had luggage with me, and luggage and cobbled hills don't really match. This time, I could have a ramble round. It had turned into a perfect spring day by the time I got there...

First destination: Salt's Mill. Built in 1853 by Titus Salt for textile production, and the heart of the planned community which surrounds it.

Textile production ended in the 1980s, and the mill was bought by Jonathan Silver. Since then, it's been converted into a series of galleries, shops and restaurants, and contains a huge collection of works by local boy David Hockney. This is the ground floor gallery

There were some beautiful pots. Some William de Morgan, some Islamic, some local.

These ones are Burmantofts - I hadn't heard of them before, but they're local, and from a company much better known for tiles and architectural features. Fabulous things.

View from the ladies' loo window...

After a lovely smoked chicken salad at Salt's Diner, and a poke around the shops (think I've managed to stock up on cards and small gifts for the next six months or so!), I thought I'd do the walk round the village suggested in the official guidebook.

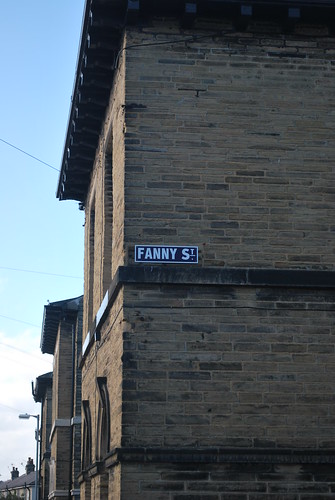

Other than Albert Street and Victoria Street, all the others are named after members of Titus Salt's family.

Some of these names work better in a modern context than others.

Here are some of the more humble houses

(following the modern rule that Where There Shall Be Houses, There Shall Be Wheeliebins. I'm hoping it's bin day, rather than that being the permanent situation - we used to play in the lane like that behind our house when we were kids).

Here are some of the rather posher ones, belonging to overseers.

Signs of spring

There are also almshouses

and a concert hall (the Victoria Hall, of course)

and, right next to the station, a pub. As you can see from the name, not in the original town plan. Salt doesn't appear to have been anti-alcohol - the mill-owned shops in the village would do off-sales - but preferred to build educational public spaces.

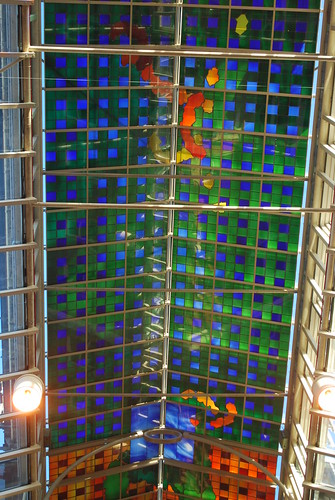

After a restorative pint, I went back to Leeds in mid-afternoon, and had a wander round the city centre. Missed the covered market (due to lack of sense of direction), but found the Victoria Quarter and its rather spectacular stained-glass roofs

and one of my favourite shops - stand aside, Harvey Nicks, this town has a Clas Ohlson! Realise that not everyone's idea of holiday shopping is buying locks, hacksaws and cleaning materials; I love Clas Ohlson but don't get to Norwich very often...

Looking for somewhere to eat on the way back to the station, I again got lost, but heading downhill always seems to be a good move. I ended up in a Pizza Express (lack of research again!), but it was right next to St Paul's House, a spectacular Hispano-Moorish construction; former cloth-cutting mill which now seems to be full of lawyers.

I was shattered on the train home and the next day, but it was completely worth it - hills, sunshine, Yorkshire and its sense of solid Victoriana, yarn... Lovely day.

Just after Christmas, East Coast had a sale; a ridiculously good sale. Wasn't able to pin family down to dates within the timescale, and there weren't many trains on a Sunday in the offer, so I thought "Wonder how far I can go for £5 each way?" and the answer was York or Leeds. I love York; but I love Leeds more, and all I've done there for the last many years is change train, occasionally popping out of the station for a quick meal between journeys.

I set off at 5:35am from the village (first train out; only the second time I've done that), so by 9:30 I'd got to Leeds, bought my onward ticket, and wandered out to City Square.

As you can see, it's a bit wet; but the forecast for the rest of the day was good. And there was a happy sight on the way out of the station; Leeds is seriously cheerful about the Grand Départ in July.

(This year, I'm abandoning the French pronunciation of Grand and doing it in a Yorkshire voice in my head...)

Normally, I'm really organised on a visit; this time, other than the tiny map in the Kindle version of the Rough Guide and a quick look-up of bus routes, I was entirely unprepared for the trip after what had felt like an extraordinarily long week. I also have absolutely no sense of direction, which is always interesting in a strange city, even one I visited briefly last year. But I had a destination in prospect, and Leeds has lots of maps around at road junctions, so I found the bus stop, and the no. 1 bus; and I reached my destination about 2 minutes before it was due to open. Looked promising!

The extremely nice Baa Ram Ewe (Headingley branch); just opposite a big shopping centre, but based in a converted cottage; about 15 minutes from the city centre by bus. The person in the shop was American, and lovely, and I realised afterwards we hadn't exchanged names (sorry, lovely yarn-shop lady!); conversation ranged from London commuting to Yarndale to the beautiful yarns they had from West Yorkshire Spinners.

One of my aims was to fondle some of their own Titus yarn, as I hadn't managed to get anywhere near their booth at Yarndale, particularly given my final destination. A skein of duck-eggy-green, very springlike (Bramley Baths), has accompanied me home, along with a coordinating Crazy Zauberball; once the current knitting project is done that'll be the next thing on the needles! (Also picked up some gift yarn and a couple of skeins of discounted Colinette.)

All yarned-up, I got the bus back into Leeds and a train out to Saltaire. I've been through Saltaire so many times on the way to Keighley for the SkipNorth holiday, and every time I've promised myself that next time... I'd stop. But I've always had luggage with me, and luggage and cobbled hills don't really match. This time, I could have a ramble round. It had turned into a perfect spring day by the time I got there...

First destination: Salt's Mill. Built in 1853 by Titus Salt for textile production, and the heart of the planned community which surrounds it.

Textile production ended in the 1980s, and the mill was bought by Jonathan Silver. Since then, it's been converted into a series of galleries, shops and restaurants, and contains a huge collection of works by local boy David Hockney. This is the ground floor gallery

There were some beautiful pots. Some William de Morgan, some Islamic, some local.

These ones are Burmantofts - I hadn't heard of them before, but they're local, and from a company much better known for tiles and architectural features. Fabulous things.

After a lovely smoked chicken salad at Salt's Diner, and a poke around the shops (think I've managed to stock up on cards and small gifts for the next six months or so!), I thought I'd do the walk round the village suggested in the official guidebook.

Other than Albert Street and Victoria Street, all the others are named after members of Titus Salt's family.

Some of these names work better in a modern context than others.

Here are some of the rather posher ones, belonging to overseers.

Signs of spring

and a concert hall (the Victoria Hall, of course)

and, right next to the station, a pub. As you can see from the name, not in the original town plan. Salt doesn't appear to have been anti-alcohol - the mill-owned shops in the village would do off-sales - but preferred to build educational public spaces.

and one of my favourite shops - stand aside, Harvey Nicks, this town has a Clas Ohlson! Realise that not everyone's idea of holiday shopping is buying locks, hacksaws and cleaning materials; I love Clas Ohlson but don't get to Norwich very often...

Looking for somewhere to eat on the way back to the station, I again got lost, but heading downhill always seems to be a good move. I ended up in a Pizza Express (lack of research again!), but it was right next to St Paul's House, a spectacular Hispano-Moorish construction; former cloth-cutting mill which now seems to be full of lawyers.

2014 books, #21-25

Lost river, by Stephen Booth. London: Harper, 2011.

On May Bank Holiday afternoon, Ben Cooper pulls a dead child from a river; the incident is immediately traumatic, but there seems to be something more than accidental death involved and Cooper is led to investigate the girl's family. Meanwhile, Diana Fry is reliving trauma of her own - new DNA evidence has been found by West Midlands police, and the case is Diane's own rape, the event which sent her to Derbyshire in the first place. This is a slightly disjointed book because of the two settings, and to me there are some slightly strained (and possibly stereotypical) elements - Fry's taking the law into her own hands to the extent she does doesn't seem in character; but the coming-together of the two very disparate plots into similar themes (won't say more, spoilers!) is so skilfully done that Booth's allowed the benefit of the doubt here!

Vengeance [Mystery Writers of America presents...]. Edited by Lee Child. London: Corvus, 2012. [Kindle edition.]

A volume of short stories around the theme of vengeance. As ever with these anthologies, it's a mixed bag; but some of these stories are extraordinarily good. Unfortunately, as I never seem to get around to blogging books from the Kindle, I can't really remember which were which! There are some big names here, as you'd expect from a book with Child's pulling power - Child himself, Michael Connelly, Dennis Lehane and Karin Slaughter, but also some newer authors like Dreda Say Mitchell and Alafair Burke. (And as far as I remember, it was a very good cheap offer on Kindle at the time!)

A fatal thaw, by Dana Stabenow. [Kate Shugak 2]. Kindle edition.

I got these for Kindle last autumn, but was waiting until it was a bit warmer to read them - they're set in Alaska and Stabenow is extremely good at showing us how cold it is! Kate Shugak is caught up despite her will in another murder; nine of her neighbours have been killed by a man running amok with a hunting rifle. As investigations continue though, it seems that one of the dead was actually murdered with a different weapon, and just about everyone in the area had a potential motive. Kate and her motley crew of sidekicks including a part-wolf, part-Husky called Mutt and a disabled Vietnam veteran called Bobby take on the case, at some personal cost.

Dead in the water, by Dana Stabenow. [Kate Shugak 3]. Kindle edition.

This time, Kate is investigating the deaths of two crew members on a crab-boat in the Aleutian islands (yes, possibly even colder than the last book) by joining the crew. The work is extraordinarily hard but also pretty lucrative, but she suspects the captain and permanent crew members of having alternative sources of income. She also needs to protect her very young, very naïve roommate Andy from their colleagues, and while she has her usual backup from Jack Morgan on land, she's at sea on her own in every sense. As someone who's part-Aleut, she is also drawn to the people of the islands and their culture, which adds another element of interest.

Meet me in Malmö, by Torquil MacLeod. Kindle edition.

Ewan Strachan, a washed-up arts journalist from Newcastle, goes to Malmö to interview an old college friend, Mick Roslyn, now a successful film director with a film-star wife. When he gets to Mick and Malin's flat, he finds Malin dead and no sign of Mick. Strachan is held in Malmö, filing despatches about the murder investigation and travel pieces, while inspector Anita Sunderstrom investigates. Meanwhile, we're finding out things about Strachan and Roslyn's relationship, which involves the suspicious death of a woman 25 years before. I wasn't massively convinced by this book; there are too many unconvincing twists and turns, and unlike with masters of these (like Deaver), you can see the mechanism too closely. The end also has a very unconvincing last bite in it. Not necessarily recommended, although it starts off very well.

On May Bank Holiday afternoon, Ben Cooper pulls a dead child from a river; the incident is immediately traumatic, but there seems to be something more than accidental death involved and Cooper is led to investigate the girl's family. Meanwhile, Diana Fry is reliving trauma of her own - new DNA evidence has been found by West Midlands police, and the case is Diane's own rape, the event which sent her to Derbyshire in the first place. This is a slightly disjointed book because of the two settings, and to me there are some slightly strained (and possibly stereotypical) elements - Fry's taking the law into her own hands to the extent she does doesn't seem in character; but the coming-together of the two very disparate plots into similar themes (won't say more, spoilers!) is so skilfully done that Booth's allowed the benefit of the doubt here!

Vengeance [Mystery Writers of America presents...]. Edited by Lee Child. London: Corvus, 2012. [Kindle edition.]

A volume of short stories around the theme of vengeance. As ever with these anthologies, it's a mixed bag; but some of these stories are extraordinarily good. Unfortunately, as I never seem to get around to blogging books from the Kindle, I can't really remember which were which! There are some big names here, as you'd expect from a book with Child's pulling power - Child himself, Michael Connelly, Dennis Lehane and Karin Slaughter, but also some newer authors like Dreda Say Mitchell and Alafair Burke. (And as far as I remember, it was a very good cheap offer on Kindle at the time!)

A fatal thaw, by Dana Stabenow. [Kate Shugak 2]. Kindle edition.

I got these for Kindle last autumn, but was waiting until it was a bit warmer to read them - they're set in Alaska and Stabenow is extremely good at showing us how cold it is! Kate Shugak is caught up despite her will in another murder; nine of her neighbours have been killed by a man running amok with a hunting rifle. As investigations continue though, it seems that one of the dead was actually murdered with a different weapon, and just about everyone in the area had a potential motive. Kate and her motley crew of sidekicks including a part-wolf, part-Husky called Mutt and a disabled Vietnam veteran called Bobby take on the case, at some personal cost.

Dead in the water, by Dana Stabenow. [Kate Shugak 3]. Kindle edition.

This time, Kate is investigating the deaths of two crew members on a crab-boat in the Aleutian islands (yes, possibly even colder than the last book) by joining the crew. The work is extraordinarily hard but also pretty lucrative, but she suspects the captain and permanent crew members of having alternative sources of income. She also needs to protect her very young, very naïve roommate Andy from their colleagues, and while she has her usual backup from Jack Morgan on land, she's at sea on her own in every sense. As someone who's part-Aleut, she is also drawn to the people of the islands and their culture, which adds another element of interest.

Meet me in Malmö, by Torquil MacLeod. Kindle edition.

Ewan Strachan, a washed-up arts journalist from Newcastle, goes to Malmö to interview an old college friend, Mick Roslyn, now a successful film director with a film-star wife. When he gets to Mick and Malin's flat, he finds Malin dead and no sign of Mick. Strachan is held in Malmö, filing despatches about the murder investigation and travel pieces, while inspector Anita Sunderstrom investigates. Meanwhile, we're finding out things about Strachan and Roslyn's relationship, which involves the suspicious death of a woman 25 years before. I wasn't massively convinced by this book; there are too many unconvincing twists and turns, and unlike with masters of these (like Deaver), you can see the mechanism too closely. The end also has a very unconvincing last bite in it. Not necessarily recommended, although it starts off very well.

2014 books, #16-20

A land more kind than home, by Wiley Cash [audiobook]. Read by Lorna Raver, Mark Bramhall and Nick Sullivan. Rearsby, Leics.: Clipper, 2012.

Based on a true event. An autistic child is smothered during a "healing" service in a snake-wrangling church in North Carolina; the violence which follows in investigated by a sheriff with his own tragedies in the past, and his own axe to grind. The writing here is sometimes astonishingly moving, and the situation - faith, infidelity and the failure of a community to protect its children - very tragic. The multiple narratives wind around each other (this is possibly one where the audiobook format works at its best), and the conclusion is as shocking as it is inevitable. A very, very good book.

Racing hard: 20 tumultuous years in cycling, by William Fotheringham. London: Guardian/Faber, 2013.

I was interested in cycling in the late 80s when living in France, and subsequently watching the Tour highlights in sports bars after a day at the archaeological-finds-classifying tables, but from about 1993 until four years ago, I'd completely lost touch with the world of professional cycling. This book fills in those gaps wonderfully with accounts of the development of the Tour and its characters, and of the development of the current crop of British cyclists (culminating in Wiggins's win in the 2012 Tour, and the 2012 London Olympics and Paralympics). Fotheringham has written on many more subjects than this but he's decided to confine his scope to those two events here. He combines the viewpoint of the fan with that of the relative insider - his obvious disappointment and distress at the various drugs scandals is clear - and while he could have edited some of his articles extensively, he's reprinted them unedited, with rueful notes on the benefit of hindsight. Great book.

Gone in seconds, by A J Cross [audiobook]. Read by Anna Bentinck. Oxford: Isis, 2013.

When the skeleton of a young woman is found near a West Midlands motorway, evidence suggests that it is that of teenager Molly James, who went missing five years ago. Forensic psychologist Dr Kate Hanson and the Unsolved Crime Unit are called in to re-investigate Molly's case. The deeper they dig the dirtier the clues get, and when a second set of remains is unearthed Kate suspects they're looking for a Repeater: a killer who will adapt, grow and not stop until they are caught. She also suspects that not all of her colleagues are as keen on investigating the case as she is. Good; tightly plotted.

The shock of the fall, by Nathan Filer. London: HarperCollins, 2013.

This year's Costa winner, and an astonishing book. The narrator is a mentally ill 19-year-old boy, writing consciously for publication, whose illness seems to have been precipitated by events around the death of his older brother, who had Down's Syndrome, ten years before. 'I'll tell you what happened because it will be a good way to introduce my brother. His name's Simon. I think you're going to like him. I really do. But in a couple of pages he'll be dead. And he was never the same after that.' The account's both a diary and a memoir, and the text changes font and breaks up at different times to reflect Matt's state of mind. Not a cheerful book, although it's not without hope, but a fascinating read.

The daylight gate, by Jeanette Winterson. London: HarperCollins, 2012.

Written to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the Pendle witch trials, this contains as much sex, violence and persecution as you might expect. Winterson weaves her tale around Alice Nutter, the only witch from the middle classes who was executed at Pendle. In Winterson's version (which she freely admits to be at least part fantasy), Alice makes her fortune by the invention of a colourfast magenta dye beloved of Elizabeth I, and has been in London with John Dee and Shakespeare; she has learned the secret of the elixir of youth from Dr Dee; and she is sheltering Christopher Southworth, one of the Guy Fawkes plotters and a Catholic priest. This is a wild, swirling fantasy which dips in and out of historical events while getting its feet completely soaked in the filth and squalour of the era.

Based on a true event. An autistic child is smothered during a "healing" service in a snake-wrangling church in North Carolina; the violence which follows in investigated by a sheriff with his own tragedies in the past, and his own axe to grind. The writing here is sometimes astonishingly moving, and the situation - faith, infidelity and the failure of a community to protect its children - very tragic. The multiple narratives wind around each other (this is possibly one where the audiobook format works at its best), and the conclusion is as shocking as it is inevitable. A very, very good book.

Racing hard: 20 tumultuous years in cycling, by William Fotheringham. London: Guardian/Faber, 2013.

I was interested in cycling in the late 80s when living in France, and subsequently watching the Tour highlights in sports bars after a day at the archaeological-finds-classifying tables, but from about 1993 until four years ago, I'd completely lost touch with the world of professional cycling. This book fills in those gaps wonderfully with accounts of the development of the Tour and its characters, and of the development of the current crop of British cyclists (culminating in Wiggins's win in the 2012 Tour, and the 2012 London Olympics and Paralympics). Fotheringham has written on many more subjects than this but he's decided to confine his scope to those two events here. He combines the viewpoint of the fan with that of the relative insider - his obvious disappointment and distress at the various drugs scandals is clear - and while he could have edited some of his articles extensively, he's reprinted them unedited, with rueful notes on the benefit of hindsight. Great book.

Gone in seconds, by A J Cross [audiobook]. Read by Anna Bentinck. Oxford: Isis, 2013.

When the skeleton of a young woman is found near a West Midlands motorway, evidence suggests that it is that of teenager Molly James, who went missing five years ago. Forensic psychologist Dr Kate Hanson and the Unsolved Crime Unit are called in to re-investigate Molly's case. The deeper they dig the dirtier the clues get, and when a second set of remains is unearthed Kate suspects they're looking for a Repeater: a killer who will adapt, grow and not stop until they are caught. She also suspects that not all of her colleagues are as keen on investigating the case as she is. Good; tightly plotted.

The shock of the fall, by Nathan Filer. London: HarperCollins, 2013.

This year's Costa winner, and an astonishing book. The narrator is a mentally ill 19-year-old boy, writing consciously for publication, whose illness seems to have been precipitated by events around the death of his older brother, who had Down's Syndrome, ten years before. 'I'll tell you what happened because it will be a good way to introduce my brother. His name's Simon. I think you're going to like him. I really do. But in a couple of pages he'll be dead. And he was never the same after that.' The account's both a diary and a memoir, and the text changes font and breaks up at different times to reflect Matt's state of mind. Not a cheerful book, although it's not without hope, but a fascinating read.

The daylight gate, by Jeanette Winterson. London: HarperCollins, 2012.

Written to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the Pendle witch trials, this contains as much sex, violence and persecution as you might expect. Winterson weaves her tale around Alice Nutter, the only witch from the middle classes who was executed at Pendle. In Winterson's version (which she freely admits to be at least part fantasy), Alice makes her fortune by the invention of a colourfast magenta dye beloved of Elizabeth I, and has been in London with John Dee and Shakespeare; she has learned the secret of the elixir of youth from Dr Dee; and she is sheltering Christopher Southworth, one of the Guy Fawkes plotters and a Catholic priest. This is a wild, swirling fantasy which dips in and out of historical events while getting its feet completely soaked in the filth and squalour of the era.

Wednesday, March 05, 2014

2014 books, #11-15

Sycamore Row, by John Grisham. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2013.

This is a (very belated) sequel to A time to kill, which was made into an extremely good film. Like the previous chapter of Jake Brigance's story, it's set in the 1980s. Unlike the previous chapter, this is a civil case about a will. Seth Hubbard hangs himself, after posting a handwritten will and covering letter to Jake; the will leaves 90% of his fortune to his (black) housekeeper and revokes a previous testament leaving substantial amounts to Seth's children. Jake is again in the middle of a viper's nest (and increasingly disenchanted once race comes into the story), and when the principal beneficiary is swooped on by lawyers with an axe to grind, he's on the verge of throwing in the towel. As ever with Grisham, if you're alert you can see the ending coming way ahead; but it's still worth reading for all that.

No rest for the dead, by various authors. London: Simon and Schuster, 2012.

When the dead body of Christopher Thomas, a ruthless curator at San Francisco’s McFall Art Museum, is found bloodied and decaying in an iron maiden in a museum in Berlin, his wife is the primary suspect. Rosemary Thomas is tried, convicted, and executed, but ten years later, Detective Jon Nunn remains convinced that the wrong person was put to death. This is a collaboration between over 20 authors, most of them extremely well-known, each taking a chapter. The chapters are cleverly allocated - Kathy Reichs writes up the forensic reports, Jeffery Deaver presides over a chapter with a couple of the switchback turns he's notorious for, and so on - and the writing remarkably even. Good plot, and an interesting project; all profits to leukaemia and lymphoma research.

The late scholar: Peter Wimsey investigates. Based on the characters of Dorothy L Sayers, by Jill Paton Walsh. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2013.

Another excellent Wimsey novel; Paton Walsh treads a fine line between pastiche, fanfiction and new fiction, and comes out on the right side of the line on all counts. Along with his unwanted Dukedom, Peter has inherited a position as the Visitor at St Severin's College, Oxford, and is called in as the final arbiter in a bitter college dispute which has already proved fatal for at least one of St Severin's dons, and may have accounted for the Warden, too. And someone is using methods from Peter's cases (as recounted in Harriet's novels) to try and despatch academics. Really excellent.

Breakdown, by Sara Paretsky [audiobook]. Read by Liza Ross. Oxford: Isis, 2012.

A group of schoolgirls who've gathered in a cemetery to re-enact Carmilla stories (a sort of Twilight-type series of novels for tweens) find a dead body on a slab. They're not a typical group of girls, though - one is the granddaughter of a billionaire, another is the daughter of a Democratic Senate candidate and two of the others are the children of an illegal immigrant, at the exclusive school on scholarships. All are now in danger, and VI Warshawski's cousin, a classroom assistant at the school, calls in VI to help. As she does so, she is dragged into a web of deceit and personal danger. There are, as ever, a couple of slightly unlikely elements in the plot, but it's a very good one and stretches from 1940s Poland to the present day.

The bones of Paris, by Laurie R. King. London: Allison and Busby, 2013.

A follow-up to Touchstone, although you probably don't have to have read that one to enjoy this. Harris Stuyvesant is in Paris in 1929, hired by an American family to find their missing daughter. While searching, he discovers she may not have been the only missing person to have disappeared in similar circumstances, and is drawn into the circle of a fashionable elite including Man Ray and Picasso, and the macabre world of the Grand-Guignol and a fetishism of death. King slips into the world of the period without obvious anachronisms. Genuinely scary in parts, and as ever tightly-plotted.

This is a (very belated) sequel to A time to kill, which was made into an extremely good film. Like the previous chapter of Jake Brigance's story, it's set in the 1980s. Unlike the previous chapter, this is a civil case about a will. Seth Hubbard hangs himself, after posting a handwritten will and covering letter to Jake; the will leaves 90% of his fortune to his (black) housekeeper and revokes a previous testament leaving substantial amounts to Seth's children. Jake is again in the middle of a viper's nest (and increasingly disenchanted once race comes into the story), and when the principal beneficiary is swooped on by lawyers with an axe to grind, he's on the verge of throwing in the towel. As ever with Grisham, if you're alert you can see the ending coming way ahead; but it's still worth reading for all that.

No rest for the dead, by various authors. London: Simon and Schuster, 2012.

When the dead body of Christopher Thomas, a ruthless curator at San Francisco’s McFall Art Museum, is found bloodied and decaying in an iron maiden in a museum in Berlin, his wife is the primary suspect. Rosemary Thomas is tried, convicted, and executed, but ten years later, Detective Jon Nunn remains convinced that the wrong person was put to death. This is a collaboration between over 20 authors, most of them extremely well-known, each taking a chapter. The chapters are cleverly allocated - Kathy Reichs writes up the forensic reports, Jeffery Deaver presides over a chapter with a couple of the switchback turns he's notorious for, and so on - and the writing remarkably even. Good plot, and an interesting project; all profits to leukaemia and lymphoma research.

The late scholar: Peter Wimsey investigates. Based on the characters of Dorothy L Sayers, by Jill Paton Walsh. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2013.

Another excellent Wimsey novel; Paton Walsh treads a fine line between pastiche, fanfiction and new fiction, and comes out on the right side of the line on all counts. Along with his unwanted Dukedom, Peter has inherited a position as the Visitor at St Severin's College, Oxford, and is called in as the final arbiter in a bitter college dispute which has already proved fatal for at least one of St Severin's dons, and may have accounted for the Warden, too. And someone is using methods from Peter's cases (as recounted in Harriet's novels) to try and despatch academics. Really excellent.

Breakdown, by Sara Paretsky [audiobook]. Read by Liza Ross. Oxford: Isis, 2012.

A group of schoolgirls who've gathered in a cemetery to re-enact Carmilla stories (a sort of Twilight-type series of novels for tweens) find a dead body on a slab. They're not a typical group of girls, though - one is the granddaughter of a billionaire, another is the daughter of a Democratic Senate candidate and two of the others are the children of an illegal immigrant, at the exclusive school on scholarships. All are now in danger, and VI Warshawski's cousin, a classroom assistant at the school, calls in VI to help. As she does so, she is dragged into a web of deceit and personal danger. There are, as ever, a couple of slightly unlikely elements in the plot, but it's a very good one and stretches from 1940s Poland to the present day.

The bones of Paris, by Laurie R. King. London: Allison and Busby, 2013.

A follow-up to Touchstone, although you probably don't have to have read that one to enjoy this. Harris Stuyvesant is in Paris in 1929, hired by an American family to find their missing daughter. While searching, he discovers she may not have been the only missing person to have disappeared in similar circumstances, and is drawn into the circle of a fashionable elite including Man Ray and Picasso, and the macabre world of the Grand-Guignol and a fetishism of death. King slips into the world of the period without obvious anachronisms. Genuinely scary in parts, and as ever tightly-plotted.